Abel transform

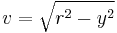

In mathematics, the Abel transform, named for Niels Henrik Abel, is an integral transform often used in the analysis of spherically symmetric or axially symmetric functions. The Abel transform of a function f(r) is given by:

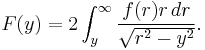

Assuming f(r) drops to zero more quickly than 1/r, the inverse Abel transform is given by

In image analysis, the forward Abel transform is used to project an optically thin, axially symmetric emission function onto a plane, and the reverse Abel transform is used to calculate the emission function given a projection (i.e. a scan or a photograph) of that emission function.

In absorption spectroscopy of cylindrical flames or plumes, the forward Abel transform is the integrated absorbance along a ray with closest distance y from the center of the flame, while the inverse Abel transform gives the local absorption coefficient at a distance r from the center. Abel transform is limited to applications with axially symmetric geometries. For more general asymmetrical cases, more general-oriented reconstruction algorithms such as Algebraic Reconstruction Technique (ART), Maximum Likelihood Expectation Maximization (MLEM), Filtered Back-Projection (FBP) algorithms should be employed.

In recent years, the inverse Abel transformation (and its variants) has become the cornerstone of data analysis in photofragment-ion imaging and photoelectron imaging. Among recent most notable extensions of inverse Abel transformation are the Onion Peeling and BAsis Set Expansion (BASEX) methods of photoelectron and photoion image analysis.

Contents |

Geometrical interpretation

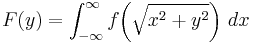

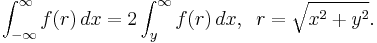

In two dimensions, the Abel transform F(y) can be interpreted as the projection of a circularly symmetric function f(r) along a set of parallel lines of sight which are a distance y from the origin. Referring to the figure on the right, the observer (I) will see

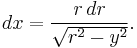

where f(r) is the circularly symmetric function represented by the gray color in the figure. It is assumed that the observer is actually at x = ∞ so that the limits of integration are ±∞ and all lines of sight are parallel to the x-axis. Realizing that the radius r is related to x and y via r2 = x2 + y2, it follows that

The path of integration in r does not pass through zero, and since both f(r) and the above expression for dx are even functions, we may write:

Substituting the expression for dx in terms of r and rewriting the integration limits accordingly yields the Abel transform.

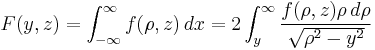

The Abel transform may be extended to higher dimensions. Of particular interest is the extension to three dimensions. If we have an axially symmetric function f(ρ,z) where ρ2 = x2 + y2 is the cylindrical radius, then we may want to know the projection of that function onto a plane parallel to the z axis. Without loss of generality, we can take that plane to be the yz-plane so that

which is just the Abel transform of f(ρ,z) in ρ and y.

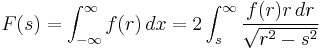

A particular type of axial symmetry is spherical symmetry. In this case, we have a function f(r) where r2 = x2 + y2 + z2. The projection onto, say, the yz-plane will then be circularly symmetric and expressible as F(s) where s2 = y2 + z2. Carrying out the integration, we have:

which is again, the Abel transform of f(r) in r and s.

Verification of the inverse Abel transform

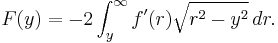

Assuming f is continuously differentiable and f, f' drop to zero faster than 1/r, we can set  and

and  . Integration by parts then yields

. Integration by parts then yields

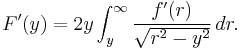

Differentiating formally,

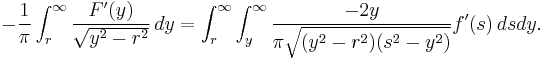

Now plug this into the inverse Abel transform formula:

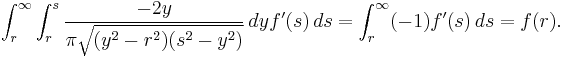

By Fubini's theorem, the last integral equals

Generalization of the Abel transform to discontinuous F(y)

Consider the case where  is discontinuous at

is discontinuous at  , where it abruptly changes its value by a finite amount

, where it abruptly changes its value by a finite amount  . That is,

. That is,  and

and  are defined by

are defined by ![\Delta F \equiv \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0} [ F(y_\Delta-\epsilon) - F(y_\Delta%2B\epsilon) ]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1c069dc67b6ffd9ec6da569b68e169af.png) . Such a situation is encountered in tethered polymers (Polymer brush) exhibiting a vertical phase separation, where

. Such a situation is encountered in tethered polymers (Polymer brush) exhibiting a vertical phase separation, where  stands for the polymer density profile and

stands for the polymer density profile and  is related to the spatial distribution of terminal, non-tethered monomers of the polymers.

is related to the spatial distribution of terminal, non-tethered monomers of the polymers.

The Abel transform of a function f(r) is under these circumstances again given by:

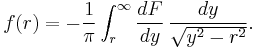

Assuming f(r) drops to zero more quickly than 1/r, the inverse Abel transform is however given by

where  is the Dirac delta function and

is the Dirac delta function and  the Heaviside step function. The extended version of the Abel transform for discontinuous F is proven upon applying the Abel transform to shifted, continuous

the Heaviside step function. The extended version of the Abel transform for discontinuous F is proven upon applying the Abel transform to shifted, continuous  , and it reduces to the classical Abel transform when

, and it reduces to the classical Abel transform when  . If

. If  has more than a single discontinuity, one has to introduce shifts for any of them to come up with a generalized version of the inverse Abel transform which contains n additional terms, each of them corresponding to one of the n discontinuities.

has more than a single discontinuity, one has to introduce shifts for any of them to come up with a generalized version of the inverse Abel transform which contains n additional terms, each of them corresponding to one of the n discontinuities.

Relationship to other integral transforms

Relationship to the Fourier and Hankel transforms

The Abel transform is one member of the FHA cycle of integral operators. For example, in two dimensions, if we define A as the Abel transform operator, F as the Fourier transform operator and H as the zeroth-order Hankel transform operator, then the special case of the Projection-slice theorem for circularly symmetric functions states that:

In other words, applying the Abel transform to a 1-dimensional function and then applying the Fourier transform to that result is the same as applying the Hankel transform to that function. This concept can be extended to higher dimensions.

Relationship to the Radon transform

The Abel transform is a projection of f(r) along a particular axis. The two-dimensional Radon transform gives the Abel transform as a function of not only the distance along the viewing axis, but of the angle of the viewing axis as well.

References

- Bracewell, R. (1965). The Fourier Transform and its Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-007016-4.

![f(r)=\left[ \frac{1}{2}\delta(r-y_\Delta)\sqrt{1-(y_\Delta/r)^2} - \frac{1}{\pi} \frac{H(y_\Delta-r)}{\sqrt{y_\Delta^2-r^2}} \right] \Delta F-\frac{1}{\pi}\int_r^\infty\frac{d F}{dy}\frac{dy}{\sqrt{y^2-r^2}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2be199716280aaf6005b3ea9b40b04ab.png)